Haber process

The Haber process, also called the Haber–Bosch process, is the nitrogen fixation reaction of nitrogen gas and hydrogen gas, over an enriched iron or ruthenium catalyst, which is used to industrially produce ammonia.[1][2][3][4]

Despite the fact that 78.1% of the air we breathe is nitrogen, the gas is relatively unavailable because it is so unreactive: nitrogen molecules are held together by strong triple bonds. It was not until the early 20th century that the Haber process was developed to harness the atmospheric abundance of nitrogen to create ammonia, which can then be oxidized to make the nitrates and nitrites essential for the production of nitrate fertilizer and explosives. Prior to the discovery of the Haber process, ammonia had been difficult to produce on an industrial scale.

The Haber process is important today because the fertilizer generated from ammonia is responsible for sustaining one-third of the Earth's population.[5] It is estimated that half of the protein within human beings is made of nitrogen that was originally fixed by this process, the remainder was produced by nitrogen fixing bacteria and archaea.[6]

Contents |

History

Early in the twentieth century, several chemists tried to make ammonia from atmospheric nitrogen. German chemist Fritz Haber discovered a process that is still used today. Robert Le Rossignol was instrumental in the development of the high-pressure devices used in the Haber process. They demonstrated their process in the summer of 1909 by producing ammonia from air drop by drop, at the rate of about 125 ml (4 US fl oz) per hour. The process was purchased by the German chemical company BASF, which assigned Carl Bosch the task of scaling up Haber's tabletop machine to industrial-level production.[2][7] Haber and Bosch were later awarded Nobel prizes, in 1918 and 1931 respectively, for their work in overcoming the chemical and engineering problems posed by the use of large-scale, continuous-flow, high-pressure technology. Ammonia was first manufactured using the Haber process on an industrial scale in 1913 in BASF's Oppau plant in Germany. During World War I, production was shifted from fertilizer to explosives, particularly through the conversion of ammonia into a synthetic form of Chile saltpeter, which could then be changed into other substances for the production of gunpowder and high explosives (the Allies had access to large amounts of saltpeter from natural nitrate deposits in Chile that belonged almost totally to British industries. Therefore, Germany had to produce its own). It has been suggested that without this process, Germany would not have fought the war,[8] or would have had to surrender years earlier.

The process

By far the major source of the hydrogen required for the Haber-Bosch process is methane from natural gas, obtained through a heterogeneous catalytic process, which requires far less external energy than the process used initially by Bosch at BASF: the electrolysis of water. Far less commonly, in some countries, coal is used as the source of hydrogen through a process called coal gasification. The source of the hydrogen is of no consequence in the Haber-Bosch process.

Synthesis gas preparation

The methane is first cleaned, mainly to remove sulfur oxide and hydrogen sulfide impurities that would poison the catalysts.

The clean methane is then reacted with steam over a catalyst of nickel oxide. This is called steam reforming:

- CH4 + H2O → CO + 3 H2

Secondary reforming then takes place with the addition of air to convert the methane that did not react during steam reforming:

- 2 CH4 + O2 → 2 CO + 4 H2

- CH4 + 2 O2 → CO2 + 2 H2O

Then the water gas shift reaction yields more hydrogen from CO and steam:

- CO + H2O → CO2 + H2

The gas mixture is now passed into a methanator[9] which converts most of the remaining CO into methane for recycling:

- CO + 3 H2 → CH4 + H2O

This last step is necessary as carbon monoxide poisons the catalyst. (Note, this reaction is the reverse of steam reforming). The overall reaction so far turns methane and steam into carbon dioxide, steam, and hydrogen.

Ammonia synthesis – Haber process

The final stage, which is the actual Haber process, is the synthesis of ammonia using an iron catalyst promoted with K2O, CaO and Al2O3:

- N2 (g) + 3 H2 (g) ⇌ 2 NH3 (g) (ΔH = −92.22 kJ·mol−1)

This is done at 15–25 MPa (150–250 bar) and between 300 and 550 °C, as the gases are passed over four beds of catalyst, with cooling between each pass so as to maintain a reasonable equilibrium constant. On each pass only about 15% conversion occurs, but any unreacted gases are recycled, and eventually an overall conversion of 97% is achieved.

The steam reforming, shift conversion, carbon dioxide removal, and methanation steps each operate at absolute pressures of about 2.5–3.5 MPa (25–35 bar), and the ammonia synthesis loop operates at absolute pressures ranging from 6–18 MPa (59–178 atm), depending upon which proprietary design is used.

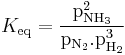

Reaction rate and equilibrium

There are two opposing considerations in this synthesis: the position of the equilibrium and the rate of reaction. At room temperature, the reaction is slow and the obvious solution is to raise the temperature. This may increase the rate of the reaction but, since the reaction is exothermic, it also has the effect, according to Le Chatelier's principle, of favouring the reverse reaction and thus reducing the amount of product, given by:

| Temperature (°C) | Keq |

|---|---|

| 300 | 4.34 x 10−3 |

| 400 | 1.64 x 10−4 |

| 450 | 4.51 x 10−5 |

| 500 | 1.45 x 10−5 |

| 550 | 5.38 x 10−6 |

| 600 | 2.25 x 10−6 |

As the temperature increases, the equilibrium is shifted and hence, the amount of product drops dramatically according to the Van't Hoff equation. Thus one might suppose that a low temperature is to be used and some other means to increase rate. However, the catalyst itself requires a temperature of at least 400 °C to be efficient.

Pressure is the obvious choice to favour the forward reaction because there are 4 moles of reactant for every 2 moles of product (see entropy), and the pressure used (around 200 atm) alters the equilibrium concentrations to give a profitable yield.

Economically, though, pressure is an expensive commodity. Pipes and reaction vessels need to be strengthened, valves more rigorous, and there are safety considerations of working at 200 atm. In addition, running pumps and compressors takes considerable energy. Thus the compromise used gives a single pass yield of around 15%.

Another way to increase the yield of the reaction would be to remove the product (i.e. ammonia gas) from the system. In practice, gaseous ammonia is not removed from the reactor itself, since the temperature is too high; but it is removed from the equilibrium mixture of gases leaving the reaction vessel. The hot gases are cooled enough, whilst maintaining a high pressure, for the ammonia to condense and be removed as liquid. Unreacted hydrogen and nitrogen gases are then returned to the reaction vessel to undergo further reaction.

Catalysts

The catalyst has no effect on the position of chemical equilibrium; rather, it provides an alternative pathway with lower activation energy and hence increases the reaction rate, while remaining chemically unchanged at the end of the reaction. The first Haber–Bosch reaction chambers used osmium and ruthenium as catalysts. However, under Bosch's direction in 1909, the BASF researcher Alwin Mittasch discovered a much less expensive iron-based catalyst that is still used today. Part of the industrial production now takes place with a ruthenium rather than an iron catalyst (the KAAP process), because this more active catalyst allows reduced operating pressures.

In industrial practice, the iron catalyst is prepared by exposing a mass of magnetite, an iron oxide, to the hot hydrogen feedstock. This reduces some of the magnetite to metallic iron, removing oxygen in the process. However, the catalyst maintains most of its bulk volume during the reduction, and so the result is a highly porous material whose large surface area aids its effectiveness as a catalyst. Other minor components of the catalyst include calcium and aluminium oxides, which support the porous iron catalyst and help it maintain its surface area over time, and potassium, which increases the electron density of the catalyst and so improves its activity.

The reaction mechanism, involving the heterogeneous catalyst, is believed to be as follows:

- N2 (g) → N2 (adsorbed)

- N2 (adsorbed) → 2 N (adsorbed)

- H2(g) → H2 (adsorbed)

- H2 (adsorbed) → 2 H (adsorbed)

- N (adsorbed) + 3 H(adsorbed)→ NH3 (adsorbed)

- NH3 (adsorbed) → NH3 (g)

Reaction 5 occurs in three steps, forming NH, NH2, and then NH3. Experimental evidence points to reaction 2 as being the slow, rate-determining step.

A major contributor to the elucidation of this mechanism is Gerhard Ertl.[11][12][13][14]

Economic and environmental aspects

The Haber process now produces 500 million tons (453 billion kilograms) of nitrogen fertilizer per year, mostly in the form of anhydrous ammonia, ammonium nitrate, and urea. 3–5% of world natural gas production is consumed in the Haber process (~1–2% of the world's annual energy supply).[1][15][16][17] That fertilizer is responsible for sustaining one-third of the Earth's population, but results in various deleterious environmental consequences.[2][5] Hydrogen production using electrolysis of water powered by renewable energy is not yet competitive with hydrogen from fossil fuels, such as natural gas. As of 2007, only 5% of hydrogen is produced by electrolysis.[18] Notably, the rise of the Haber industrial process led to the "Nitrate Crisis" in Chile when the natural nitrate mines were no longer profitable and were closed, leaving a large unemployed Chilean population behind.

See also

References

- ^ a b Enriching the Earth: Fritz Haber, Carl Bosch, and the Transformation of World Food Production by Vaclav Smil (2001) ISBN 0-262-19449-X

- ^ a b c Hager, Thomas (2008). The Alchemy of Air. Harmony Books, New York. ISBN 9780307351784.

- ^ Fertilizer Industry: Processes, Pollution Control and Energy Conservation by Marshall Sittig (1979) Noyes Data Corp., N.J. ISBN 0-8155-0734-8

- ^ "Heterogeneous Catalysts: A study Guide"

- ^ a b Wolfe, David W. (2001). Tales from the underground a natural history of subterranean life. Cambridge, Mass: Perseus Pub. ISBN 0738201286. OCLC 46984480.

- ^ BBC: Discovery - Can Chemistry Save The World? - 2. Fixing the Nitrogen Fix

- ^ US Pat 990191

- ^ "Nobel Award to Haber". New York Times. 3 February 1920. http://query.nytimes.com/mem/archive-free/pdf?_r=1&res=9807EEDA133BEE32A25750C0A9649C946195D6CF&oref=slogin. Retrieved 11 October 2010.

- ^ "Methanator". http://infos.mpip.free.fr/siemens/Chromatographe/Methanator_En_1.0.pdf.

- ^ Chemistry the Central Science" Ninth Ed., by: Brown, Lemay, Bursten, 2003, ISBN 0-13-038168-3

- ^ F. Bozso, G. Ertl, M. Grunze and M. Weiss (1977). "Interaction of nitrogen with iron surfaces: I. Fe(100) and Fe(111)". Journal of Catalysis 49 (1): 18–41. doi:10.1016/0021-9517(77)90237-8.

- ^ R. Imbihl, R. J. Behm, G. Ertl and W. Moritz (1982). "The structure of atomic nitrogen adsorbed on Fe(100)". Surface Science 123 (1): 129–140. doi:10.1016/0039-6028(82)90135-2.

- ^ G. Ertl, S. B. Lee and M. Weiss (1982). "Kinetics of nitrogen adsorption on Fe(111)". Surface Science 114 (2–3): 515–526. doi:10.1016/0039-6028(82)90702-6.

- ^ G. Ertl (1983). "Primary steps in catalytic synthesis of ammonia". Journal of Vacuum Science and Technology a 1 (2): 1247–1253. doi:10.1116/1.572299.

- ^ "International Energy Outlook 2007". http://www.eia.doe.gov/oiaf/ieo/nat_gas.html.

- ^ "?". http://www.fertilizer.org/ifa/statistics/indicators/ind_reserves.asp.

- ^ Smith, Barry E. (September 2002). "Structure. Nitrogenase reveals its inner secrets". Science 297 (5587): 1654–5. doi:10.1126/science.1076659. PMID 12215632.

- ^ Peter Häussinger, Reiner Lohmüller, Allan M. Watson “Hydrogen” Ullmann's Encyclopedia of Industrial Chemistry, 2002, Wiley-VCH, Weinheim. doi:10.1002/14356007.a13_297

- "The Haber Process". Chemguide.co.uk. http://www.chemguide.co.uk/physical/equilibria/haber.html.

External links

- Haber-Bosch process, most important invention of the 20th century, according to V. Smil, Nature, July 29, 1999, p 415 (by Jürgen Schmidhuber)

- Britannica guide to Nobel Prizes: Fritz Haber

- Nobel e-Museum - Biography of Fritz Haber

- Uses and Production of Ammonia

- Haber Process for Ammonia Synthesis